LUCY BURDETTE: I don't know Daria, but when I heard about her new book, I wanted to! I asked our past guest Laura Hankin to connect us. I hope you'll enjoy her post and her book as much as I did. Welcome Daria!

DARIA LAVELLE: There’s an old adage in storytelling—show, don’t tell. In other words, let the reader experience a narrative through its visual cues (set the scene; describe the action; create the characters). Most stories are written this way, with descriptions that enable a reader to picture exactly what’s going on, and of course that’s critical to a compelling story. But just showing neglects the other senses.

When sound, touch, smell, or taste—for me, especially taste—enter the chat, it heightens a story, making it not just something I can picture in my mind, but something I can experience in my body. A good food description can (and often does) make me physically drool (or recoil, or gag, or smack my lips). Food is such a powerful avenue for storytelling, but it’s often underused in fiction, leveraged just to highlight a character cultural background or their typical eating habits.

But it can be so much more.

Recently, on the UK leg of my book tour for Aftertaste, a novel which is, unsurprisingly, obsessed with food, I had the extraordinary experience of dining at a restaurant called The Fat Duck. It’s been on my bucket list for ages, and not only because it boasts 3 Michelin stars. I’ve been aching to eat there because the Chef Heston Blumenthal treats each meal as an immersive experience, one that uses every sense to tell a story about each dish, and also about the meal at large. Some examples? Okie dokie.

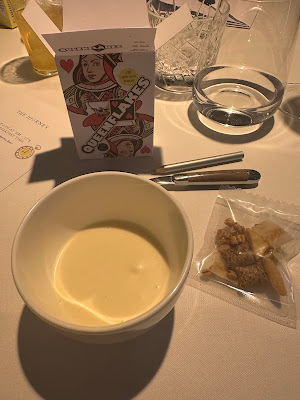

One course, which was an appetizer, was made to look exactly like a child's breakfast. You were presented with a bowl of “milk” and a miniature cereal box—each of these different and custom printed to include fun quips and puns about the restaurant and the food world, as well as a cereal box game you could play with the pencil that came in the box. Inside, was a pouch of “cereal” which you opened and poured into your "milk." Only, when you ate it, it was clear this was not cereal. It was magic. A savory, jelly-rich, pudding with these perfectly crisped flakes for crunch. It was delicious, but more than that, it was nostalgic. It transported you to the delight of eating cereal on a Sunday morning, and doing the puzzles with your kid brother.

Another course, which was meant to bring back the fun and whimsy of being at the seaside as a kid, started with miniature ice cream cones—crab bisque ice cream—and continued with a pair of headphones, which you donned to hear recordings from the beach (surf, sand, gulls, kids laughing and splashing) while you ate a dish made to look (I kid you not) exactly like the edge of sand meeting seafoam, where every component—the sand, the foam, the miniature “jelly fish” and “seaweed” and “shells” that had washed up on the shore—was edible. Eating that dish felt more like being at the beach than having my toes in actual sand. It captured the feel of those moments, their exact texture. It unlocked memories.

I won’t go on—I could, at length—but it was the most magical meal partly because I had no idea what to expect, and I would hate to ruin it for others. But the point I’m making is that food can be so much more than ornamentation or accessory; it can be the story. To eat is to storytell. To cook, even more so. Food is memory, and memory makes character.

When I approached writing food in Aftertaste, where a chef can taste the most significant meals of ghosts from the spirit world, and recreate the dishes to bring them back for a last meal with their loved ones, every ingredient in every dish did the double duty of carrying the emotional weight of memory. When a particular character ate the potatoes in a particular kind of soup, for instance, their rough skin didn’t remind her of an itchy sweater or a fraying picnic bench; they reminded her of a particular kind of clothing worn at her convent, because that clothing brought her to the person she longed to see again. Try it in your own storytelling, and see what happens, and how it energizes your text. Steep your characters’ foods in emotional meaning, and watch the flavors it gives your scene, or your chapter, or your whole book.

Taste, in other words. Don’t just tell.

Daria Lavelle is an American fiction writer. Born in Kyiv, Ukraine, and raised in the New York City area, her work explores themes of identity and belonging through magic and the uncanny. Her short stories have appeared in The Deadlands, Dread Machine, and elsewhere, and she holds degrees in writing from Princeton University and Sarah Lawrence College. She lives in New Jersey with her husband, children, and goldendoodle, all of whom love a great meal almost as much as she does. Learn more at darialavelle.com.

Synopsis of Aftertaste:

What if you could have one last meal with someone you loved, someone you lost?

Konstantin Duhovny is a haunted man. His father died when he was ten, and ghosts have been hovering around him ever since. Kostya can’t exactly see the ghosts, but he can taste their favorite foods. Flavors of meals he’s never eaten will flood his mouth,a sign that a spirit is present. Kostya has kept these aftertastes a secret for most of his life, but one night, he decides to act on what he’s tasting. And everything changes.

Kostya discovers that he can reunite people with their deceased loved ones—at least for the length of time it takes them to eat a dish that he’s prepared. Convinced that his life’s purpose is to offer closure to grieving strangers, he sets out to learn all he can by entering a particularly fiery ring of Hell: the New York culinary scene. But as his kitchen skills catch up with his ambitions, Kostya is too blind to see the catastrophe looming in the Afterlife. And the one person who knows Kostya must be stopped also happens to be falling in love with him.

Set in the bustling world of New York restaurants and teeming with mouthwatering food writing, Aftertaste is a whirlwind romance, a heart-wrenching look at love and loss, and a ghost story about all the ways we hunger—and how far we’d go to find satisfaction.